Catch Returns

The trout fishing season has ended. I should be sad, but I’m not. I’m stressed. Its demise signifies an awkward time for a traditional angler like me. Not that I’m worried about a season ending (seasonality in angling is what keeps our sport balanced and in tune with Nature) but because it marks the time when I have to get statistical about my fishing. It is time to submit a catch return.

Thinking about how many, or few, trout I’ve caught in a season is no more meaningful than calculating how many times I’ve worn a favourite hat. The ‘enter total here’ box just doesn’t appeal. Total what? I go fishing for reasons other than catching fish.

I don’t like trying to quantify emotion, or rationalising pleasure, at all. Doing so is like describing a sunset as ‘8.47pm’. That we smiled and have happy memories is enough. But obligations are obligations. The catch return must be submitted. I’m sorry, but I’m going to have to get serious. It’s time to do some numeric reasoning.

Submitting a catch return is a complicated business. One has to remember exactly the number, species and size of fish caught; when and on what fly they succumbed to your net; from which beat of the river they came and at what time of day; and in what weathers, atmospheric pressures and wind speeds you decided to take a pee. In fact, all the unimportant and boring things that can’t determine whether you had a good season. But record them we must – to appease someone who likes statistics and most probably carries a tape measure with him when fishing. (I guess it’s to ‘measure his pleasure’, done when no one else is looking. You can imagine it, can’t you, "A-rise! Aha! There you are! No point tugging! I’m going lay you out, run this tape along you and then plot you on a graph!”)

It’s fair to say that presenting me with numbers is like asking Ghandi to bungee jump off an elephant. I can add, subtract, divide, multiply and count to a thousand and thirty-seven. (Anyone who’s counted beyond that must have been in serious need of entertainment.) Calculus and algebra were never my strengths at school and mental arithmetic was exactly that: mental. They might as well have been the names of psychotic French footballers. Which is why I need your help. I’ve only caught three trout this season, so I’m going to need you to help me with some creative accounting.

The truth is that I’ve spent more time walking the river this year than fishing it. Even when I have caught a fish I’ve reeled in, sat back, and spent the remainder of the day drinking tea and watching the clouds float by. (Mrs H says I’m the most easily distracted person she knows. It’s not at all true. Ooh. Hang on. What were we talking about? Oh yes. I need your help to complete my catch return.)

We could go straight to the creative part, perhaps recording the fish in weight of drams, or by the number of spots on their flanks? But as I said, I’ve got to be serious about this. I need to be strict. I’ll have to invite you to an interview.

If you want the job, you’ll need to read the following case study, answer four questions and then present the correct overall answer. You can use an abacus, calculator, fingers or toes, but be sure to record your answer, which you’ll need to present as a one-hour slide presentation later on. Ready? Okay. Here goes:

The Case Study:

Archie Wangumout goes fishing to catch fish. He fishes four times per week from April to October inclusive and two times per week for the remainder of the year. He catches, on average, five fish per visit and doesn’t believe in catch and release. In the second week of May he fished a dry fly and caught twenty-nine trout. His January fish weighed 2lbs each but he noticed that the average weight of fish declined by two per cent per month, although his largest trout was an 8lb 4oz specimen caught in September. He fished a 9ft 6in rod with a 7-weight line for thirty-three per cent of the time, an 8ft rod with a 4-weight line for twenty per cent of the time and a 10ft lightning-hurler for the remainder. Archie is

47 years old, single and his goal in life is to increase his catch rate by eighteen per cent.

- Question One: Is Archie a total loser, or what?

- Question Two: Will you give him a kicking or should I?

- Question Three: How long will it be before he gets sponsored for his efforts?

- Question Four (the one requested by the Fishery Officer): What is the square root of the number of the fish caught; added to the median weight of individual fish taken between May and September inclusive; divided by the average length of rod based upon time used; then multiplied by pie?

How did you get on? Did the case study make you sweat, curse and rub your brow, even before you’d seen the questions? Well done for persevering. I’ll give you the answer later. For now, let’s get back to the task at hand: debating why numbers are not important in fishing. (It’s true. I do get easily distracted.)

Recording numerical information is all very well and good for someone who counts beans, but not for an angler. Doing so only proves the urge to tally away one’s life, like notches on a bedpost in an empty house. "He’s a great angler,” they will say, "He caught his thousandth salmon this week.” Hmm. It depends what you mean by great. Or accomplished. Or contented. The fish, sadly, is just a number, added to a list of other numbers. We don’t know what it looked like, how it fought, whether it was returned, or if the angler even smiled when he caught it. It is just number 1000, destined to be replaced by number 1001 and a whole load more until the angler reaches number 1037 and realises he’s in serious need of meaningful entertainment. He’ll then take up golf, or darts, or snooker, or any other sport where a number determines his enjoyment. The end result will still be the same: One-Nil, where nil stands for ‘Never Investigated Life’.

It’s the same with those who weigh or measure their catch. Again, the fish becomes a number:

"I caught six doubles this season.”

"Interesting, I didn’t know you watched tennis?”

"My average was eleven and a half.”

"You mean eleven point five.”

"Yes.”

"I thought you had.”

"Had what?”

"Lost the point.”

As for the other so-called ‘recordable details’, like fly choice and weather, they at least document something that paints an image in one’s memory. It’s a bit like knowing that a toad explodes at exactly 14 psi when you attach it to an air pump. But there are better ways of describing the seasons and documenting one’s memories. I’ll give you an example. Think of your favourite holiday…

What first came to mind? I’ll wager that it wasn’t ‘atmospheric pressure 1013 millibars’? Most likely you were happy, optimistic, excited and contented. All are emotional states which made the holiday feel special and which, in turn, made it memorable. If angling is also special, then why think of it or record it in any other way than how it made us feel? For example, you’ve just been fishing and had the most wonderful day. But you caught nothing. Do you enter the word ‘blank’ in your diary? Or do you write something like, "Fished the Windrush – mayflies dancing in the evening sun – fledgling marsh tits twittering in the willows – primroses in flower – trout rising lazily – two token casts – happy just to sit and watch the sunset.” As my friend Phin’ says, "It’s the anecdotes and incidents that make up a day. When we remember them, we’re there, anecdotally and incidentally.”

Here’s the point I most want to make:

We are human beings who each experience our own journey through life, guided by our unique view of the world.

Our memories, therefore, are our own. Only we know what we thought and – more importantly – how we felt. It’s these feelings that get stored in our memory banks. One usually remembers how something made us feel more so than the details behind why we felt it.

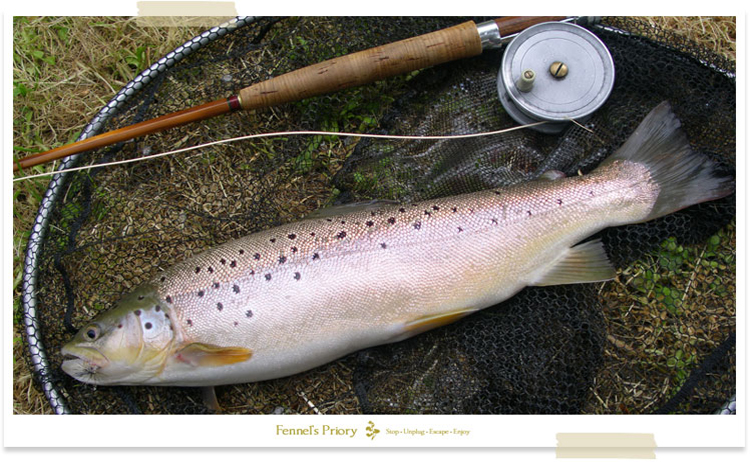

So how do you feel now about completing that catch return? The fishery manager will want us to report the facts – that Fennel caught three brown trout, each around the two-pounds mark. One on a Mayfly, one on a Goldhead Damsel and one on a Parachute Adams; two from the Windrush and one from the club lake. "But what was your catch ratio?” he will ask. "Three fish from how many trips?” The fact of the matter is I can’t remember. It might be ten, or twenty, or thirty trips. Or it might be none. I might have made it up. I think I’ll put "0.5” in the return and let him do the maths.

Postscript:

My apologies, I forgot to give you the answer to the final interview question. If you got "10.29” or indeed anything involving numbers, then I’m sorry, you haven’t got the job. If, however, you made your calculations based upon the Priory Principles of Numeric Reasoning then you’ll have realised that there’s a range of answers: chicken and mushroom, mince beef, steak and kidney, to name but a few. I’ll go with steak and kidney, perhaps with some new potatoes and runner beans. That’s my sort of memory.

This is a sample chapter from Fly Fishing, Fennel's Journal No. 5

If you like the work of lifestyle and countryside author Fennel Hudson, then please subscribe to Fennel on Friday. You'll receive a blog, video or podcast sent direct to your email inbox in time for the weekend.