Firelight

It is 11 o’clock on a cold, windswept and rainy February night. Mrs H and Little Lady are upstairs, sleeping peacefully beneath quilted blankets, and I am downstairs in the living room, penning letters to my friends and doing my bit to stay awake past midnight (so to enjoy the tranquil silence of ‘the zero hour’).

I am writing by firelight – one of the softest, gentlest, and most welcoming of lights. It glints upon the golden nib of my fountain pen, reminding me of the life outdoors that I bring inside whenever I write about nature. (Though I always remember Mark Twain’s advice that "words are only painted fire, a look is the fire itself.”) Firelight is undisputedly a living light, much like that of a candle, but it has the ability to warm a room, toast a late-night crumpet, and keep a man up past bedtime. Such are the suppertime delights of the fireside writer…

I like fires. They are pleasant, homely, atmospheric, and cherished.

Or rather I like wood fires. (Coal, when burned, produces foul-smelling smoke that reminds me of car exhaust and the pollution of heavy industry. Also it has a blue-green flame that looks rather ‘other-worldly’. Sure, it kicks out plenty of heat, but what use is warmth when you don’t want to stand next to it?) The flames in the fire by my side come from boughs of ash – the aptly named king of firewoods. It produces blight, clean flames and burns steadily for ages, making me immensely happy.

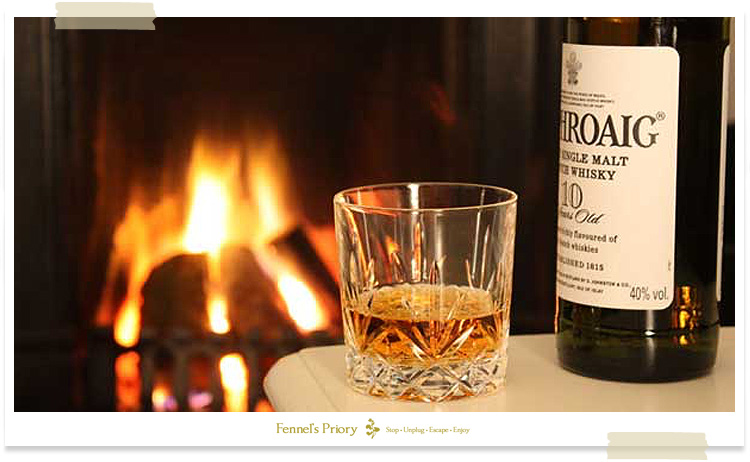

My mood is lifted not just by the fire, but also by the presence of a cut-glass tumbler and more than a wee dram of Islay single malt. The peaty, smoky taste of the whisky complements the aroma of the fire, and its amber hues capture and accentuate the beauty of the firelight. It is a taste and glimpse of yesteryear (ten years, to be precise) mingling with the present, like Cine Film images projected upon a wall. It’s much the same with firelight. Each flame releases yesterday’s sunlight, which cuts through darkened rooms or sullen moods with its summer brightness. A fire is, as Henry David Thoreau said, "the main comfort of the camp, whether in summer or winter … as well for cheerfulness as for warmth and dryness.” Sitting quietly beside a fire, therefore, is a ritual designed to warm us in more ways than one. As I recently found out.

An elderly friend of mine lives alone in a Victorian house near to the River Thames. The building has no central heating, and the only modern improvements are three-pin electric plug sockets and a telephone. It’s a virtual museum –nicely vintage but nastily antique –full of period features like condensation on the walls, mould on the carpet, and draughts coming from every window and door. Just the sort of place that breeds pneumonia and, perversely, a desire for a traditionalist like me to live there. But my friend is housebound due to illness, and doesn’t get many visitors except for his angling chums who call in on their way back from the river. I saw him last week and, instead of us talking about the never-ending rain and how it’s threatening the non-existent damp-proof course of his house, we talked, rather buoyantly (if you’ll excuse the pun), of how floodwater brings many gifts to the astute ‘rivercomber’.

"Flotsam, or jetsam?” asked my friend. "I’m never sure which one is which? One floats and settles; the other gets stuck in things. Correct? Floodwater brings us all sorts of goodies that are there for the taking once the river levels subside. Once I found a perfectly usable oar stuck in the branches of a willow. I walked another fifty yards downriver and found another one just like it. Never found the boat they came from, but I did find a perfectly intact garden shed, complete with hammock and parasol. I brought them home, dried them out, and now they are valued additions to my garden. The shed is especially liked. I use it as my log shed, to dry-out firewood that my friends find for me on their travels.” He paused for a second, and then attempted to look behind me, "Talking of which, did you bring any?”

"Erm, no, sorry,” I replied. "I never thought to look.”

"Pity,” replied my friend, as his gaze returned to the fireplace. "The river provides all my firewood: from twigs for kindling, to tree-trunks for splitting and seasoning. A good flood will wash them down and leave them in the fields for my friends to collect. But I suppose you were too distracted by your angling instincts to see the real value of a flood?”

"Perhaps,” I replied, wishing my fisherman’s blinkers to be removed.

"Next time you’re by the river,” my friend continued, "keep your eyes open for firewood. Oak, ash, hawthorn and blackthorn are best. Beech and hornbeam are good, but have to be seasoned for at least a year. Orchard trees like cherry and apple burn with a delightful perfume, but one has to weigh-up whether to burn them or turn them on a lathe – such is their beauty. Willow is ‘okay’ but spits and burns rather too quickly, as does pine with its sticky smoke that coats the chimney and threatens chimney fires.”

My friend leant forward, tilted his head and looked upwards at the chimneybreast, then whispered, "I once found a telegraph pole washed down by the floods. It was infused with creosote and coated in tar. I sawed and chopped it up, then stuck it on the fire. Whoosh! It burned like a flamethrower rumbling in the grate. Kept going for ages, and I was delighted until my neighbours crowded outside the house, pointing at the black smoke billowing out of my chimney. It was one of those ‘note to self’ moments, that if I’m going to smoke high tar logs, then I’d better fit a filter tip to the chimney pot first.”

"Sounds dangerously warming!” I said, raising my eyebrows and leaning away from the fire that burned in his living room. "I’m glad you know what you’re doing. You’ve obviously got this wood-burning craft down to a fine art.”

"Not so much an art, Fennel,” he replied, "More…” he paused for a few seconds and then said, "…a necessity. I need a fire for more than warmth. I need it for company.”

"How so?”

"Living alone has its benefits, but also its limitations. This is a lonely house at night. Sometimes I fear going to bed in case I wake up in the early hours and find myself unable to get back to sleep. I’m surrounded by cold darkness that clings to my skin. That’s why I always put a couple of oak logs on the fire before I go to bed, so they can burn slowly through the night. That way, should I wake up, I can go downstairs and sit beside the fire – for company. It talks to me y’see – like a beacon lit atop a mountain. There’s always a message in a fire. Crackling and popping, it asks me whether I’m all right and reassures me that the emptiness of night is only a temporary endurance. My mood lifts and the character of the house improves – changing from prison to home. That’s why a fire’s important. It’s the heart of a home. It warms and comforts me, in so many ways. I’m never alone beside a wood fire.”

And so, as I sip my whisky and write these words, I gaze over at the fire that burns next to me. I realise that its heat, or rather its warmth, doesn’t do much radiate as permeate. It reaches deep within us, evoking thoughts of friendship and good times.

We can stare into its flames and be reminded of so many things, so many places and people. It’s like a portal bringing messages of hope, reminding us of what’s important.

For that is the beauty of firelight: it puts everything into perspective.

This is a sample chapter from The Lighter Side, Fennel's Journal No. 10

If you like the work of lifestyle and countryside author Fennel Hudson, then please subscribe to Fennel on Friday. You'll receive a blog, video or podcast sent direct to your email inbox in time for the weekend.