A Lakeside Camp

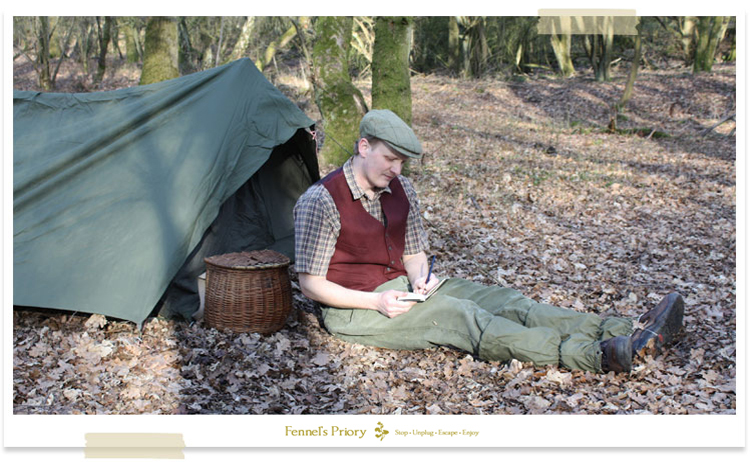

Well, this is it. Our time by the lake begins. (I say ‘our’ time, because, as Lord Byron wrote, "Letter writing is the only device for combining solitude with good company”.) Mrs H-to-be, who brought me here, has helped me to unload my camping and ‘survival’ gear and has now departed for some quality time at home. I have carried everything up into the woods, set up camp, got a fire started and made a brew. I am now sitting on a carpet of beech and oak leaves, with notepad on my knee, pen in hand and a mug of tea on the ground beside me. The disturbance of my arrival has subsided. Calm has descended and I feel at one with my new surroundings.

It’s amazing how quickly this wood and the lake have welcomed my presence. I’ve camped in similar places before, often detecting a coldness that targets one’s spine and makes it difficult to properly relax. Not so today. Today the air is fresh and inviting. I want to hold my hands aloft and smile. For I am free. A good start, given that I’ve only been here for a few hours.

I set up camp, as planned, in a small clearing in the woods. A vast tree stump (the diameter of which must be five feet) marks the centre of the clearing. I intend to use it as a dining table for when I’m feeling civil, but for now it is the gravestone of a once-mighty beech that grew here. Next to the stump is my tent: a two-man ex-army canvas job that, I’m pleased to say, has a built-in groundsheet. It doesn’t look like much but, as an estate agent might say, "It is air conditioned and with exceptional location”. Inside the tent is stored a canvas rucksack, brass Primus stove, billy cans, Kelly Kettle, Tilley lamp, bow saw, tinned food, chorizo sausages, two loaves of bread, six pounds of butter, two-dozen eggs, quart of milk, six writing pads, three reading books, a spare change of clothes, waterproofs, wellingtons, a sleeping bag, foam mattress and thirty-six rolls of toilet paper. Oh, and an air rifle for when I need to defend the camp from bloodthirsty wolves.

I mention the contents of my tent because I want to illustrate that I have brought only the basics and that, in adventurer terms, I am of the illusion that I am ‘travelling light’. However, looking at the tent, I am now questioning whether I will be able to crawl inside it tonight. I also realise that I have forgotten to bring any fresh water (I’ve learned from experience that drinking lake water, even when boiled, has an effect on my digestive system similar to the movement of a hangman’s trapdoor). I’ve also neglected to bring a toothbrush, towel, and – how could I have been so stupid – any alcohol whatsoever. My only vice is a caddy of leaf tea that I shall reserve for those special evenings when the light is ‘just right’, when the wood pigeons coo and when the air is so still that the steam rising from my teacup drifts leisurely up through the branches of the trees to become one with the atmosphere of the place. Or I could just drink it all now and enjoy a caffeine rush that might last until morning.

My fishing tackle is stored outside the tent, although I don’t have any intention of using it just yet (the coarse-fish season doesn’t begin until the middle of June). However, it is possible to fish for trout at this time of year (their spawning has ended) and there’s a trout stream nearby. So I’ll probably seek my breakfast there. (First I’ll gauge how often it’s fished, and whether the keeper would mind me visiting every so often for ‘essential sustenance’, perhaps in exchange for a spare tin of beans or a damp loo roll.)

This camp isn’t so much about logistics, as place. I’ve carefully chosen a spot that overlooks the lake. Here, the ground is much higher than down by the dam. I’d say about thirty feet higher, which enables me to look out across – and through – the treetops to the water below. The scene is so much different to our earlier visit. The snow has melted and the buds on the trees are swelling.

The ground at the edge of the wood is carpeted with bluebells, although they look about three or four weeks away from flowering. The bird cherries are blossoming in the woods, marsh marigolds are out by the feeder stream, celandines are in bloom and arum lilies are in full leaf. The lake, in support of all the activity around it, looks like it could erupt at any moment. Its water is so very clear. Here and there are patches of bright green weed, visible in six feet of water. I can see roach dimpling the surface and carp basking in the sun. Coots and moorhens scuttle across the surface, defending their territories; a grebe is looking resplendent with its neck outstretched, attracting the ladies; and a bedraggled-looking heron stands in the sun, grateful to have made it through another winter.

Life in the wild, as I’m observing, is about survival as much as pleasure.

I remember reading Thoreau’s Walden where he speaks about keeping the internal fire going, and thinking it was merely the naïve thoughts of someone who lived in a less advanced medical age. But his were words of experience which, after my gruelling seven hours in the wilderness, I am beginning to see for their simple truth. I’m glad I packed that extra tin of chicken curry.

I might joke about my time here beside the lake, away from any likelihood of mobile phone signal or pizza delivery, but my being here is all about savouring the ‘other life’ that I once had, when I was younger and without responsibility; when days seemed to be filled with so much fun. I am, like that heron, grateful to be here. I’m grateful to be viewing such a picturesque scene and feeling so relaxed; I’m joyous to be out in the open air and hearing this fountain pen scratch across the page at an inspired speed. Being here is such a contrast to where I’d otherwise be.

At this time (it is mid-afternoon) I’d normally be sitting at work, counting the keys on my computer keyboard, or making the twelfth phoney trip to the toilet (to kill time) or wondering why my email entitled "This is not My Life!” caused such uproar with Human Resources. But time is not something to be killed. Doing so suffocates a part of us, writing off part of our life that could, or rather should, be spent doing something meaningful. Like sitting beside a lake, writing and thinking about whatever springs to mind.

I am not at work, or at the supermarket, or waiting for a bus (metaphorically or otherwise). I am free.

The final hours of the day will be spent gathering twigs for the Kelly Kettle and wood for the campfire. I might even go for a walk around the lake, to properly introduce myself, or I might leave that until tomorrow. I’m in no hurry. I might just sit here and watch the sun go down. And then I’ll go to bed, to sleep the sleep of kings.

This is a sample chapter from A Waterside Year, Fennel's Journal No. 2

If you like the work of lifestyle and countryside author Fennel Hudson, then please subscribe to Fennel on Friday. You'll receive a blog, video or podcast sent direct to your email inbox in time for the weekend.